By combining theory and practice, the material bank aims to:

For teachers and supervisors:

- Offer concrete tools to support teaching and supervisory work (teaching, psp supervision, portfolio work, etc.)

- Help understand how career readiness develops throughout the study path as a complex process

- Illustrate how and why supporting students’ career planning and expert identity development is mostly about promoting their study-related wellbeing and motivation.

For students:

- Increase students’ understanding about what career planning is all about and offer them tools for developing their career skills by integrating assignments and discussion into teaching and supervision

- Note! A dedicated set of self-study materials has been released for students under the title Tools for planning your career and future. Please inform your students about this resource!

Promoting study motivation and wellbeing

It is important to understand that supporting students’ career planning and expert identity development is mainly about promoting their study motivation and wellbeing. In her doctoral thesis, Elina Marttinen (2017) found that young adults are now more lost with their identity than ever before. She highlights how important it is for (expert) identity development that adolescents have concrete personal and career goals for their future.

Essentially, career planning is about having a holistic future orientation and working on our identity development, with the key elements being agency and meaningfulness. Professor of Career Education Tristram Hooley (2017) defines ‘career’ as a path that runs through our entire lives and includes both education and work.

According to this view, career planning has in fact begun before our university studies and will continue long after them. Every change of course in life therefore always involves career planning or future orientation – which can be either strategic or more random in nature.

It is important for students to understand what part studying plays in their career plans and what relevance and potential their expertise has for their career and other areas of life. This does not happen automatically, but requires active work.

Expertise as different forms of capital

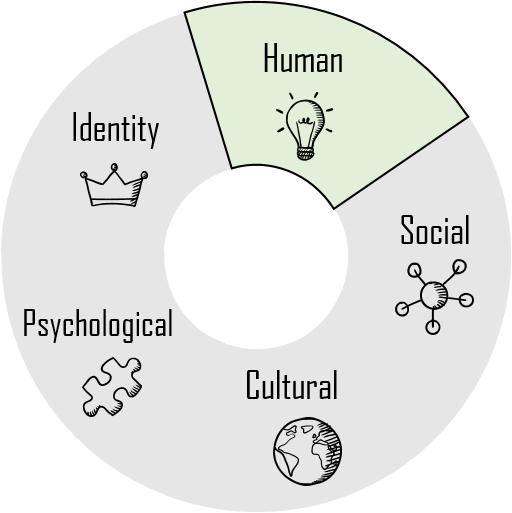

The material bank’s theoretical framework is the graduate capital model developed by Michael Tomlinson (2017), in which expertise consists of different forms of capital. In the model, employability and career readiness are categorised into five different forms of capital, whose acquisition during studies builds the basis for expert identity, career planning and the transition into the job market. Students acquire capital not only through their studies, but also through their other lived experiences.

The five forms of capital are human, social, cultural, psychological and identity capital. Of these, human capital is the most closely tied to learning and skills acquisition, whereas social capital and cultural capital are tied to the environment in which we operate. Psychological capital and identity capital are the most personal forms of capital.

The graduate capital model helps see career planning and expert identity development as a process that spans the entire study path. The challenge with individual interventions, such as individual career courses, is that for some students, they will inevitably take place at the wrong time. Moreover, key questions and requirements for different forms of capital in career planning are likely to be different for first-year and final-year students. The material bank offers tools for integrating these themes into teaching at different stages of the study path in a way that is meaningful and linked to subject-specific knowledge.

Students’ experiences as tools for teachers

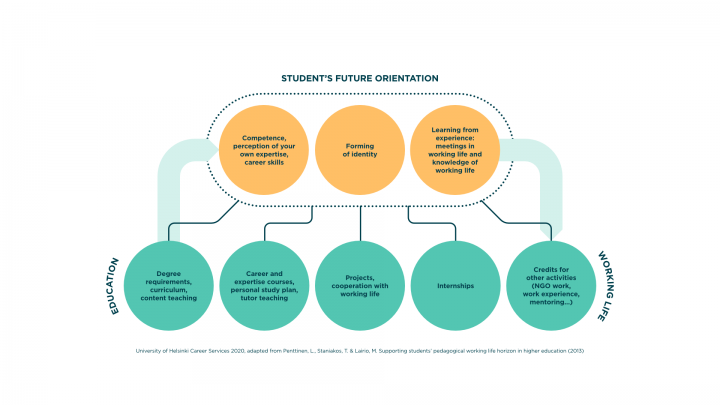

The following chart illustrates how students’ expert identity and ideas about their future develop through the experiences they acquire in their studies (and other areas of life). The process is continuous and hermeneutic: new experiences affect students’ self-perception and experiences of themselves, which in turn affects what kinds of new experiences they will seek next, and so on.

Teachers may not always see very clearly what students think about their future, but it is important to note that teachers, supervisors and the degree programme nevertheless offer students the tools that allow them to answer those questions. The blue-green circles in the chart depict these tools. By nature, these relate to the content of studies, methods of studying, practical experience and interaction, and they span the entire study path. Some of them are core study content, while others are more related to the job market, a specific industry or networking.

Supporting students’ career planning and expert identity development involves supporting the processes students go through. In providing support, it is crucial to help students find and explore the links between their studies, other life experiences and ideas about the future. The assignments included in the material bank are designed to serve this very purpose: they allow students to use their own experiences as fuel and material in planning their future, while leaving enough room for each student to approach the assignments from where they currently are in the process.

The processes of future orientation and expert identity development are unique and progress at an individual pace. However, the point where students are at in their study path will naturally affect what kind of support they need: master’s degree students have usually already developed an expert identity that is at least somewhat recognisable, whereas first-year bachelor’s degree students may find the very concept of expert identity rather remote. With doctoral students, their forms of capital and notions of the future are affected by, for example, whether they are seeking a career within or outside the university community.